🧠 [AI] rating summary

🧠 Analysis Trace

🏷️ 投资思考 (Inv-Philosophy) | 信息密度:9 | 🆕 新颖度:8 判断: 本文深度剖析了AI热潮的泡沫属性与潜在风险,提供了霍华德·马克斯式经典的投资心法警示,信息量巨大且论证严谨,但其对“是否为泡沫”的最终结论仍保持谨慎的开放性,需要读者结合自身判断。

🎯 核心信号 (The Signal)

- 一句话:AI领域正经历一场兼具巨大变革潜力和非理性繁荣的“拐点型泡沫”,投资者需以史为鉴,警惕过度投机行为和债务风险,采取审慎、有选择性的投资策略,避免财富被毁灭。

- 关键要点或时间证据链条线:

- AI被公认为有史以来最伟大的变革性技术之一,但当前市场对其的“过度热情”已具备历史泡沫的普遍特征,正处于“非理性繁荣”阶段。

- 作者区分了两类泡沫:不推动社会进步、仅毁灭财富的 “均值回归型泡沫”,以及通过投机狂热加速技术基础设施建设、为长期部署奠定基础的 “拐点型泡沫”(如铁路、互联网),AI更倾向于后者,但财富毁灭依然存在。

- AI市场存在显著的投机迹象,包括:估值脱离可预测盈利能力、大量资本涌入未有产品或盈利的初创企业(如Thinking Machines、SSI)、“彩票思维”盛行、以及大型企业在AI上的巨额资本支出。

- AI领域存在极高不确定性:未来赢家未定、技术商业化路径模糊、资产寿命及淘汰速度难测、以及“循环交易”等会计操作,这些都增加了投资风险。

- AI基础设施建设中,大规模使用债务融资,特别是对不确定性极高的项目,将极大放大潜在亏损,偏离稳健投资原则,需警惕类似2000年电信泡沫的信贷扩张和“明斯基时刻”的到来。

- 作者强调,在“赢家通吃”的技术进步中,股权投资是“正确”玩法(承担高风险高回报),而债务投资(仅赚取固定收益)则可能遭受巨额损失,尤其是在赢家难以预判的情况下。

- 面对AI带来的机遇与风险,投资者不应“全进”以规避毁灭性风险,也不应“全出”以避免错失重大技术飞跃,最佳策略是采取适度、选择性且审慎的立场。

⚖️ 立场与倾向 (Stance & Bias)

- 作者意图:深度探讨 / 警示劝诱

- 潜在偏见:谨慎悲观(作者自认非未来学家或金融乐观主义者,其投资偏好转向债券也印证其风险规避倾向,尤其在AI对就业和社会影响的后记中表达了深切忧虑,认为“情况不一样”的信念本身可能导致重蹈覆辙)。

🌲 关键实体与作用 (Entities & Roles)

- Howard Marks (霍华德·马克斯): 本文作者,Oaktree Capital Management 联合创始人,知名价值投资者,通过这篇备忘录探讨AI领域的市场过热现象与投资哲学。 ⇒ 正面

- Nvidia (英伟达): AI芯片领域的领军企业,其股价表现和高市值是AI热潮的象征,也参与了对OpenAI的投资。 ⇒ 中立

- OpenAI: AI领域的创新公司,其CEO Sam Altman的言论被引用,其高估值融资和潜在的“循环交易”引发作者关注。 ⇒ 中立

- Thinking Machines Lab / Safe Superintelligence (SSI): 被引用作为极端投机案例的AI初创公司,其在无产品或服务的情况下获得巨额高估值融资。 ⇒ 负面

- Derek Thompson: 引用其文章《人工智能可能是21世纪的铁路:做好准备》来比喻AI热潮与历史泡沫的相似性。 ⇒ 中立

- Ben Thompson (Stratechery): 引用其通讯《泡沫的好处》和 Hobart & Huber 的研究,探讨泡沫对技术进步的积极作用。 ⇒ 中立

- John Kenneth Galbraith: 引用其著作《金融狂热简史》中“金融记忆的极端短暂”观点,解释泡沫形成的人性基础。 ⇒ 中立

- Carlota Perez: 引用其著作《技术革命与金融资本》中关于泡沫“安装阶段”和“部署阶段”的理论,认为泡沫对于技术革命的必要性。 ⇒ 中立

- Gil Luria (D.A. Davidson): 金融服务公司技术研究主管,其评论被引用,区分AI行业中健康与不健康的债务使用行为。 ⇒ 中立

- Paul Kedrosky / Azeem Azhar (Exponential View): 引用其观点,警示AI基础设施融资已进入“明斯基时刻”,类似2000年电信业崩盘的风险。 ⇒ 中立

- Microsoft (微软), Amazon (亚马逊), Google (Alphabet 谷歌), Meta, Oracle (甲骨文): 拥有强大现金流的大型科技公司,被Gil Luria视为在AI领域进行“稳健投资”的代表。 ⇒ 正面

- JPMorgan (摩根大通): 其分析师对AI基础设施债务融资的估算和潜在风险(如数据中心剩余价值风险)被引用。 ⇒ 中立

- Brookfield (布鲁克菲尔德): Oaktree的母公司,正在募集巨额基金投资AI基础设施,作者强调其“审慎”使用债务的投资原则。 ⇒ 正面

- Warren Buffett (沃伦·巴菲特): 引用其关于汽车行业对早期投资者而言是灾难的观点,强调在颠覆性技术中预测赢家的难度。 ⇒ 中立

- Charles Lindbergh (查尔斯·林德伯格) / RCA: 分别作为航空业和广播无线电泡沫的历史案例,被作者比作当年的“ChatGPT”和“英伟达”。 ⇒ 中立

- Christopher Waller (克里斯托弗·沃勒) (Fed Governor): 其关于AI尚未转化为就业增长的评论,引发作者对AI潜在社会影响(失业和意义缺失)的深层忧虑。 ⇒ 中立

- Joe Davis (Vanguard 领航集团): 其关于AI对劳动时间节省和人口老龄化可能影响的观点被引用。 ⇒ 中立

💡 启发性思考 (Heuristic Questions)

- 在AI可能带来的“赢家通吃”格局下,如果无法准确识别未来的赢家,那么个人投资者应如何构建投资组合,才能既参与到这场技术革命的红利中,又最大程度规避泡沫破裂带来的财富毁灭性风险?

注:文中的加粗部分为作者Howard自己加的,表示他的强调,而文中的橙色文字是我加的颜色,并非作者Howard的强调…

original content

Ours is a remarkable moment in world history. A transformative technology is ascending, and its supporters claim it will forever change the world. To build it requires companies to invest a sum of money unlike anything in living memory. News reports are filled with widespread fears that America’s biggest corporations are propping up a bubble that will soon pop.

这是我们世界历史上的一个非凡时刻。一种变革性技术正在崛起,其支持者宣称它将永远改变世界。要构建这项技术,企业需要投入前所未有的巨额资金。新闻报道充斥着普遍的担忧:美国最大的企业正在撑起一个即将破裂的泡沫。

During my visits to clients in Asia and the Middle East last month, I was often asked about the possibility of a bubble surrounding artificial intelligence, and my discussions gave rise to this memo. I want to start off with my usual caveats: I’m not active in the stock market; I merely watch it as the best barometer of investor psychology. I’m also no techie, and I don’t know any more about AI than most generalist investors. But I’ll do my best.

上个月我在亚洲和中东拜访客户时,经常被问及人工智能是否正形成一个泡沫,这些讨论促使我撰写了这份备忘录。我想先说明我的常规提醒:我并未参与股市交易,仅将其视为投资者心理的最佳指标来观察。我也并非技术专家,对人工智能的了解并不比大多数普通投资者更多。但我会尽力而为。

One of the most interesting aspects of bubbles is their regularity, not in terms of timing, but rather the progression they follow. Something new and seemingly revolutionary appears and worms its way into people’s minds. It captures their imagination, and the excitement is overwhelming. The early participants enjoy huge gains. Those who merely look on feel incredible envy and regret and – motivated by the fear of continuing to miss out – pile in. They do this without knowledge of what the future will bring or concern about whether the price they’re paying can possibly be expected to produce a reasonable return with a tolerable amount of risk. The end result for investors is inevitably painful in the short to medium term, although it’s possible to end up ahead after enough years have passed.

泡沫最引人注目的特点之一是其发展的规律性,这并非体现在时间上,而是表现在其发展进程上。一种看似革命性的新事物出现,并逐渐渗入人们的思维。它激发了人们的想象力,令人兴奋不已。早期参与者获得了巨大的收益。而那些仅在一旁观望的人则感到难以抑制的嫉妒与懊悔,并因害怕继续错失良机而蜂拥而入。他们既不了解未来会如何,也不关心自己支付的价格是否可能带来合理回报且风险可控。最终,投资者在短期内必然遭受痛苦,尽管经过足够长的时间后,仍有可能实现盈利。

I’ve lived through several bubbles and read about others, and they’ve all hewed to this description. One might think the losses experienced when past bubbles popped would discourage the next one from forming. But that hasn’t happened yet, and I’m sure it never will. Memories are short, and prudence and natural risk aversion are no match for the dream of getting rich on the back of a revolutionary technology that “everyone knows” will change the world.

我经历过多次泡沫,也读过其他泡沫的案例,它们全都符合这一描述。人们可能会认为,过去泡沫破灭时所遭受的损失,会阻止下一次泡沫的形成。但这种情况至今尚未发生,而且我确信它永远不会发生。人们的记忆短暂,而审慎和天生的风险规避心理,根本无法抗衡“人人都知道”某种革命性技术将改变世界的致富梦想。

I took the quote that opens this memo from Derek Thompson’s November 4 newsletter entitled “AI Could Be the Railroad of the 21 st Century. Brace Yourself,” about parallels between what’s going on today in AI and the railroad boom of the 1860s. Its word-for-word applicability to both shows clearly what’s meant by the phrase widely attributed to Mark Twain: “history rhymes.”

我摘录本文开头的引言,来自德里克·汤普森 11 月 4 日发布的题为《人工智能可能是 21 世纪的铁路:做好准备》的通讯文章,该文探讨了当今人工智能的发展与 19 世纪 60 年代铁路热潮之间的相似之处。这句话在两个语境中都完全适用,这清楚地说明了马克·吐温广为流传的那句话:“历史会重演”的真正含义。

Understanding Bubbles

Before diving into the subject at hand – and having read a great deal about it in preparation – I want to start with a point of clarification. Everyone asks, “Is there a bubble in AI?” I think there’s ambiguity even in the question. I’ve concluded there are two different but interrelated bubble possibilities to think about: one in the behavior of companies within the industry, and the other in how investors are behaving with regard to the industry. I have absolutely no ability to judge whether the AI companies’ aggressive behavior is justified, so I’ll try to stick primarily to the question of whether there’s a bubble around AI in the financial world.

在深入探讨当前主题之前——在为此做了大量准备阅读之后——我想先澄清一个观点。每个人都在问:“人工智能领域是否存在泡沫?”我认为这个问题本身存在歧义。我得出的结论是,有两个不同但相互关联的泡沫可能性值得思考:一个是行业内公司行为的泡沫,另一个是投资者对行业行为的泡沫。对于人工智能公司激进行为是否合理,我完全无法判断,因此我将主要聚焦于金融世界中人工智能是否存在泡沫这一问题。

The main job of an investment analyst – especially in the so-called “value” school to which I subscribe – is to (a) study companies and other assets and assess the level of and outlook for their intrinsic value and (b) make investment decisions on the basis of that value. Most of the change the analyst encounters in the short to medium term surrounds the asset’s price and its relationship to underlying value. That relationship, in turn, is essentially the result of investor psychology.

投资分析师的主要工作——尤其是像我这样信奉所谓“价值”学派的分析师——在于(a)研究公司及其他资产,评估其内在价值水平及未来前景;(b)基于这种价值做出投资决策。分析师在短期到中期所面对的大多数变化,都围绕着资产价格与其底层价值之间的关系展开。而这一关系,本质上是投资者心理的结果。

Market bubbles aren’t caused directly by technological or financial developments. Rather, they result from the application of excessive optimism to those developments. As I wrote in my January memo On Bubble Watch, bubbles are temporary manias in which developments in those areas become the subject of what former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan called “irrational exuberance.’’

市场泡沫并非由技术或金融发展直接引发,而是这些发展被过度乐观情绪所应用的结果。正如我在一月份的《泡沫观察》备忘录中所写,泡沫是短暂的狂热现象,在这种现象中,相关领域的发展会成为前美国联邦储备委员会主席艾伦·格林斯潘所称的“非理性繁荣”的对象。

Bubbles usually coalesce around new financial developments (e.g., the South Sea Company of the early 1700s or sub-prime residential mortgage-backed securities in 2005-06) or technological progress (optical fiber in the late 1990s and the internet in 1998-2000). Newness plays a huge part in this. Because there’s no history to restrain the imagination, the future can appear limitless for the new thing. And futures that are perceived to be limitless can justify valuations that go well beyond past norms – leading to asset prices that aren’t justified on the basis of predictable earning power.

泡沫通常围绕新的金融创新(如 18 世纪初的南海公司,或 2005—2006 年的次级住宅抵押贷款支持证券)或技术进步(1990 年代末的光纤技术,以及 1998—2000 年的互联网)而形成。新颖性在其中起着至关重要的作用。由于缺乏历史经验来约束想象力,新事物的未来似乎无限广阔。而那些被认为前景无限的事物,便能为远超以往常规的估值提供合理性——从而导致资产价格脱离可预测收益能力的支撑。

The role of newness is well described in my favorite passage from a book that greatly influenced me, A Short History of Financial Euphoria by John Kenneth Galbraith. Galbraith wrote about what he called “the extreme brevity of the financial memory” and pointed out that in the financial markets, “past experience, to the extent that it is part of memory at all, is dismissed as the primitive refuge of those who do not have the insight to appreciate the incredible wonders of the present.” In other words, history can impose limits on awe regarding the present and imagination regarding the future. In the absence of history, on the other hand, all things seem possible.

新奇性的作用在我深受影响的一本书——约翰·肯尼思·加尔布雷思的《金融狂热简史》中,有一段我最喜爱的文字得到了很好的描述。加尔布雷思谈到他所谓的“金融记忆的极端短暂”,并指出在金融市场中,“过去的经验,只要它还存在于记忆之中,就被视为那些缺乏洞察力、无法理解当下惊人奇迹之人的原始避难所。”换句话说,历史可能限制我们对当下的敬畏,也限制我们对未来的想象。而在缺乏历史的情况下,一切皆有可能。

The key thing to note here is that the new thing understandably inspires great enthusiasm, but bubbles are what happen when the enthusiasm reaches irrational proportions. Who can identify the boundary of rationality? Who can say when an optimistic market has become a bubble? It’s just a matter of judgment.

这里需要注意的是,新事物自然会引发极大的热情,但当这种热情达到非理性程度时,就会形成泡沫。谁又能界定理性的边界呢?谁又能说清一个乐观的市场何时变成了泡沫呢?这终究只是判断的问题。

Something that occurred to me this past month is that two of my best “calls” came in 2000, when I cautioned about what was going on in the market for tech and internet stocks, and in 2005-07, when I cited the dearth of risk aversion and the resulting ease of doing crazy deals in the pre-Global Financial Crisis world.

上个月我突然想到,我最成功的两次“预判”分别出现在 2000 年,当时我警告过科技和互联网股票市场的异常状况;以及 2005 至 2007 年,我指出当时风险规避情绪的缺失,导致在金融危机爆发前的环境中,疯狂交易变得轻而易举。

- First, in neither case did I possess any expertise regarding the things that turned out to be the subjects of the bubbles: the internet and sub-prime mortgage-backed securities. All I did was render observations regarding the behavior taking place around me.

首先,在这两种情况下,我对最终成为泡沫主体的事物——互联网和次级抵押贷款支持证券——并无任何专业背景。我所做的只是观察身边正在发生的行为。 - And second, the value in my calls consisted mostly of describing the folly in that behavior, not in insisting that it had brought on a bubble.

其次,我的判断价值主要在于揭示这些行为中的荒谬之处,而非坚持认为它们已引发泡沫。

Struggling with whether to apply the “bubble” label can bog you down and interfere with proper judgment; we can accomplish a great deal by merely assessing what’s going on around us and drawing inferences with regard to proper behavior.

在是否使用“泡沫”这一标签的问题上犹豫不决,会让人陷入困境,干扰正确判断;我们完全可以通过评估周围正在发生的情况,并据此推断出适当的行为方式,就已取得巨大成效。

What’s Good About Bubbles? 泡沫的好处是什么?

Before going on to discuss AI and whether it’s presently in a bubble, I want to spend a little time on a subject that may seem somewhat academic from the standpoint of investors: the upside of bubbles. You may find the attention I devote to this topic excessive, but I do so because I find it fascinating.

在讨论人工智能是否目前正处于泡沫之中之前,我想花一点时间谈谈一个从投资者角度来看可能显得有些学术性的话题:泡沫的积极面。你可能会觉得我对此话题投入的关注过多,但我之所以如此,是因为我认为它非常引人入胜。

The November 5 Stratechery newsletter was entitled “The Benefits of Bubbles.” In it, Ben Thompson (no relation to Derek) cites a book titled Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation. It was written by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber, who propose that there are two kinds of bubbles:

11 月 5 日的 Stratechery 通讯文章题为《泡沫的好处》。文中,本·汤普森(与德里克无亲属关系)引用了一本名为《繁荣:泡沫与停滞的终结》的书。该书由拜恩·霍巴特和托比亚斯·胡伯撰写,他们提出泡沫可分为两种类型:

… “Inflection Bubbles” – the good kind of bubbles, as opposed to the much more damaging “Mean-reversion Bubbles” like the 2000’s subprime mortgage bubble.

……“转折点泡沫”——这种泡沫是好的,与更具破坏性的“均值回归泡沫”(如 2000 年代的次贷泡沫)形成对比。

I find this a useful dichotomy.

- The financial fads I’ve read about or witnessed – the South Sea Company, portfolio insurance, and sub-prime mortgage-backed securities – stirred the imagination based on the promise of returns without risk, but there was no expectation that they would represent overall progress for mankind. There was, for example, no thought that housing would be revolutionized by the sub-prime mortgage movement, merely a feeling that there was money to be made from backing new buyers. Hobart and Huber call these “mean-reverting bubbles,” presumably because there’s no expectation that the underlying developments would move the world forward. Fads merely rise and fall.

我所读到或亲历过的金融狂热——南海公司、投资组合保险以及次级抵押贷款支持证券——之所以激发人们的想象力,是因为它们承诺在无风险的情况下获得回报,但人们并未预期这些现象会对人类整体进步产生影响。例如,没有人认为次级抵押贷款运动将彻底改变住房行业,人们只是觉得,通过支持新购房者能赚到钱。霍巴特和胡伯将这类现象称为“均值回归型泡沫”,大概是因为人们并不认为其背后的发展会推动世界前进。这些狂热不过是昙花一现,兴起又消退。 - On the other hand, Hobart and Huber call bubbles based on technological progress – as in the case of the railroads and the internet – “inflection bubbles.” After an inflection-driven bubble, the world will not revert to its prior state. In such a bubble, “investors decide that the future will be meaningfully different from the past and trade accordingly.” As Thompson tells us:

另一方面,霍巴特和胡伯将基于技术进步的泡沫——如铁路和互联网时期的情况——称为“拐点型泡沫”。拐点型泡沫过后,世界不会回到原来的状态。在这样的泡沫中,“投资者认为未来将与过去有本质不同,因而据此进行交易。”正如汤普森所言:

The definitive book on bubbles has long been Carlota Perez’s Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital. Bubbles were – are – thought to be something negative and to be avoided, particularly at the time Perez published her book. The year was 2002 and much of the world was in a recession coming off the puncturing of the dot-com bubble.

关于泡沫的权威著作长期以来一直是卡尔洛塔·佩雷斯的《技术革命与金融资本》。人们一直认为泡沫是负面现象,应当避免,尤其是在佩雷斯出版她的著作时。那一年是 2002 年,全球大部分地区正陷入经济衰退,刚刚经历了互联网泡沫的破裂。

Perez didn’t deny the pain: in fact, she noted that similar crashes marked previous revolutions, including the Industrial Revolution, railways, electricity, and the automobile. In each case the bubbles were not regrettable, but necessary: the speculative mania enabled what Perez called the “Installation Phase,” where necessary but not necessarily financially wise investments laid the groundwork for the “Deployment Period.” What marked the shift to the deployment period was the popping of the bubble; what enabled the deployment period were the money-losing investments. (All emphasis added)

佩雷斯并未否认其中的痛苦:事实上,她指出此前历次技术革命中也出现过类似的崩盘,包括工业革命、铁路、电力以及汽车的发展。在每一种情况下,泡沫并非令人遗憾,而是必不可少的——投机狂热推动了佩雷斯所称的“安装阶段”,即那些必要但未必具有财务合理性的投资为“部署阶段”奠定了基础。从安装阶段转向部署阶段的标志是泡沫的破裂;而促成部署阶段的,则正是那些亏损的投资。(所有强调部分均加粗)

This distinction is very meaningful for Hobart and Huber, and I agree. They say, “not all bubbles destroy wealth and value. Some can be understood as important catalysts for techno-scientific progress.”

这一区分对霍巴特和胡伯而言意义重大,我亦赞同。他们指出:“并非所有的泡沫都会摧毁财富与价值。有些可以被视为科技进步的重要催化剂。”

But I would restate as follows: “Mean-reversion bubbles” – in which markets soar on the basis of some new financial miracle and then collapse – destroy wealth. On the other hand, “inflection bubbles” based on revolutionary developments accelerate technological progress and create the foundation for a more prosperous future, and they destroy wealth. The key is to not be one of the investors whose wealth is destroyed in the process of bringing on progress.

但我更愿意这样重述: “均值回归型泡沫”——即市场因某种新的金融奇迹而飙升,随后又崩溃——会摧毁财富。另一方面,“转折点型泡沫”基于革命性进展,加速技术进步并为更繁荣的未来奠定基础,同样也会摧毁财富。关键在于,不要成为在推动进步过程中财富被摧毁的投资者之一。

Hobart and Huber go on to describe in greater depth the process through which bubbles finance the building of the infrastructure required by the new technology and thus accelerate its adoption:

霍巴特和胡伯进一步深入描述了泡沫如何为新技术所需的基础设施建设提供资金,从而加速其应用的过程:

Most novel technology doesn’t just appear ex nihilo [i.e., from nothing], entering the world fully formed and all at once. Rather, it builds on previous false starts, failures, iterations, and historical path dependencies. Bubbles create opportunities to deploy the capital necessary to fund and speed up such large-scale experimentation – which includes lots of trial and error done in parallel – thereby accelerating the rate of potentially disruptive technologies and breakthroughs.

大多数创新技术并非凭空出现[即从无到有],以完整形态突然进入世界。相反,它们建立在先前的尝试失败、反复迭代以及历史路径依赖的基础之上。泡沫创造了部署必要资本的机会,以资助并加快这种大规模实验——包括大量并行进行的试错——从而加速潜在颠覆性技术与突破的进程。

By generating positive feedback cycles of enthusiasm and investment, bubbles can be net beneficial. Optimism can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Speculation provides the massive financing needed to fund highly risky and exploratory projects; what appears in the short term to be excessive enthusiasm or just bad investing turns out to be essential for bootstrapping social and technological innovations… A bubble can be a collective delusion, but it can also be an expression of collective vision. That vision becomes a site of coordination for people and capital and for the parallelization of innovation. Instead of happening over time, bursts of progress happen simultaneously across different domains. And with mounting enthusiasm… comes increased risk tolerance and strong network effects. The fear of missing out, or FOMO, attracts even more participants, entrepreneurs, and speculators, further reinforcing this positive feedback loop. Like bubbles, FOMO tends to have a bad reputation, but it’s sometimes a healthy instinct. After all, none of us wants to miss out on a once-in-a-lifetime chance to build the future.

通过制造热情与投资之间的正向反馈循环,泡沫有时也能带来总体上的益处。乐观情绪可能成为自我实现的预言。投机行为为高风险且探索性的项目提供了巨额资金;短期内看似过度的热情或糟糕的投资,实际上却是推动社会与技术革新起步的关键。……泡沫可能是一种集体错觉,但也可能是集体愿景的体现。这种愿景成为人们与资本协调的场所,也促进了创新的并行发展。进步不再随时间逐步发生,而是在不同领域同时爆发。随着热情不断高涨……风险承受能力增强,网络效应也愈发显著。错失恐惧症(FOMO)吸引着更多参与者、创业者和投机者,进一步强化了这一正向反馈循环。与泡沫类似,FOMO 往往名声不佳,但有时它其实是一种健康的本能。毕竟,我们每个人都希望抓住一生一次的机会去创造未来。

In other words, bubbles based on technological progress are good because they excite investors into pouring in money – a good bit of which is thrown away – to carpet-bomb a new area of opportunity and thus jump-start its exploitation.

换言之,基于技术进步的泡沫是好事,因为它们激发投资者投入资金——其中相当一部分最终被浪费——以地毯式轰炸的方式开拓新的机遇领域,从而推动其开发进程。

The key realization seems to be that if people remained patient, prudent, analytical, and value-insistent, novel technologies would take many years and perhaps decades to be built out. Instead, the hysteria of the bubble causes the process to be compressed into a very short period – with some of the money going into life-changing investment in the winners but a lot of it being incinerated.

关键的领悟似乎是,如果人们保持耐心、谨慎、理性分析并坚持价值投资,那么新技术的建设将需要多年甚至数十年的时间。然而,泡沫带来的狂热使这一过程被压缩到极短的时间内——一些资金投入了赢家身上,带来了改变命运的投资,但大量资金却化为灰烬。

A bubble has aspects that are both technological and financial, but the above citations are from the standpoint of people who crave technological progress and are perfectly happy to see investors lose money in its interest. “We,” on the other hand, would like to see technological progress but have no desire to throw away money to help bring it about.

泡沫既具有技术层面的特征,也具有金融层面的特征,但上述引述均来自那些渴望技术进步、并完全乐意看到投资者为这一目标蒙受损失的人。而我们则希望看到技术进步,却并不想为此随意浪费金钱。

Ben Thompson ends this discussion by saying, “This is why I’m excited to talk about new technologies, the prospect for which I don’t know.” I love the fact that he’s excited by future possibilities and at the same time admits that the shape of the future is unknown (in our world, we might say “very risky”).

本·汤普森在讨论结束时说道:“这就是为什么我对谈论新技术感到兴奋,尽管我并不知道未来会是什么样子。” 我非常欣赏他对于未来可能性的热忱,同时也认可他对未来形态未知的坦诚(在我们的世界里,或许会说“风险极高”)。

Assessing the Current Landscape

Now let’s get down to what we used to call “brass tacks.” What do we know? First, I haven’t met anyone who doesn’t believe artificial intelligence has the potential to be one of the biggest technological developments of all time, reshaping both daily life and the global economy.

现在让我们回到原本所说的“关键问题”。我们究竟知道些什么?首先,我从未遇到过一个不认为人工智能有可能成为有史以来最重大的技术突破之一的人,它将重塑日常生活和全球经济格局。

We also know that in recent years, economies and markets have become increasingly dependent on AI:

我们还知道,近年来,经济和市场对人工智能的依赖程度日益加深:

- AI is responsible for a very large portion of companies’ total capital expenditures.

人工智能占公司总资本支出的很大比例。 - Capital expenditures on AI capacity account for a large share of the growth in U.S. GDP.

对人工智能能力的资本支出在美国 GDP 增长中占据了很大份额。 - AI stocks have been the source of the vast majority of the gains of the S&P 500.

人工智能股票是标普 500 指数绝大部分涨幅的来源。

As a Fortune headline put it on October 7:

正如《财富》杂志 10 月 7 日标题所言:

75% of gains, 80% of profits, 90% of capex – AI’s grip on the S&P is total and Morgan Stanley’s top analyst is ‘very concerned’

75%的涨幅、80%的利润、90%的资本支出——人工智能对标普指数的掌控已达到全面程度,摩根士丹利首席分析师表示“非常担忧”。

Further, I think it’s important to note that whereas the gains in AI-related stocks account for a disproportionate percentage of the total gains in all stocks, the excitement AI injects into the market must have added a lot to the appreciation of non-AI stocks as well.

此外,我认为有必要指出的是,尽管与人工智能相关的股票涨幅占所有股票总涨幅的不成比例的高比例,但人工智能为市场注入的热潮也必然推动了非人工智能类股票的估值提升。

AI-related stocks have shown astronomical performance, led by Nvidia, the leading developer of computer chips for AI. From its formation in 1993 and its initial public offering in 1999, when its estimated market value was 5 trillion. That’s appreciation of around 8,000x, or roughly 40% a year for 26+ years. No wonder imaginations have been fired.

与人工智能相关的股票表现极为惊人,以人工智能芯片领域的领军企业英伟达为首。自 1993 年成立及 1999 年上市以来,当时估值约为 6.26 亿美元,英伟达曾一度成为全球首家市值突破 5 万亿美元的公司。这意味着其价值增长约 8,000 倍,相当于过去 26 年每年平均增长 40%。难怪人们的想象力被彻底点燃。

What Are the Areas of Uncertainty?

I think it’s fair to say that while we know AI will be a source of incredible change, most of us have no idea exactly what it will be able to do, how it will be applied commercially, or what the timing will be.

我认为可以公平地说,虽然我们都知道人工智能将带来翻天覆地的变化,但大多数人仍不清楚它究竟能做到什么、如何实现商业化应用,以及具体的时间表会是怎样。

Who will be the winners, and what will they be worth? If a new technology is assumed to be a world changer, it’s invariably assumed that the leading companies possessing that technology will be of great value. But how accurate will that assumption prove to be? As Warren Buffett pointed out in 1999, “[The automobile was] the most important invention, probably, of the first half of the 20 th century… If you had seen at the time of the first cars how this country would develop in connection with autos, you would have said, ‘This is the place I must be.’ But of the 2,000 companies, as of a few years ago, only three car companies survived. So autos had an enormous impact on America but the opposite direction on investors.” (Time, January 23, 2012)

谁会成为赢家,他们的价值又会如何?如果一种新技术被认为将改变世界,人们通常会假设掌握这项技术的领先公司将会具有巨大价值。但这一假设究竟有多准确呢?正如沃伦·巴菲特在 1999 年指出的:“(汽车)可能是 20 世纪前半叶最重要的发明……如果你在早期汽车出现时看到美国与汽车发展之间的关联,你一定会说:‘这就是我必须待的地方。’但就在几年前,2000 家汽车公司中只有三家幸存下来。因此,汽车对美国产生了巨大影响,却对投资者产生了相反的结果。”(《时代》杂志,2012 年 1 月 23 日)

In AI, there are some very strong leaders at present, including some of the world’s strongest and richest companies. But new technology is notoriously disruptive. Will today’s leaders prevail or give way to upstarts? How much will the arms race cost, and who will win?

在人工智能领域,目前有一些非常强大的领导者,其中包括世界上最强、最富有的几家公司。但新技术向来以颠覆性著称。今天的领军者能否持续领先,还是会败给新兴势力?这场技术军备竞赛将耗费多少成本,最终谁会胜出?

Similarly, what’s a share in an upstart worth? Unlike front runners worth trillions, it’s possible to invest in some would-be challengers at enterprise values in mere billions or even – might I say? – millions. On June 25, 2024, CNBC reported as follows:

同样地,一家新兴企业的股份价值几何?与那些市值达数万亿的领跑者不同,投资一些潜在挑战者的企业估值可能仅需数十亿,甚至——不妨说一下——数百万美元即可。2024 年 6 月 25 日,CNBC 报道称:

A team founded by college dropouts has raised $120 million from investors led by Primary Venture Partners to build a new AI chip to take on Nvidia. Etched CEO Gavin Uberti said the startup is betting that as AI develops, most of the technology’s power-hungry computing requirements will be filled by customized, hard-wired chips called ASICs. “If transformers go away, we’ll die,” Uberti told CNBC. “But if they stick around, we’re the biggest company of all time.”

由辍学大学生创立的团队已从以 Primary Venture Partners 为首的投资者那里筹集了 1.2 亿美元,用于开发一款旨在挑战英伟达的新 AI 芯片。Etched 公司首席执行官加文·乌伯蒂表示,这家初创企业赌的是,随着人工智能的发展,大部分耗电巨大的计算需求将由名为 ASIC 的定制化、硬连线芯片来满足。“如果变压器架构消失了,我们就会倒闭,”乌伯蒂对 CNBC 表示,“但如果它们继续存在,我们将成为有史以来最大的公司。”

Even granting the possibility that Etched won’t become the biggest company of all time, if success could give them a valuation just one-fifth of Nvidia’s peak – a mere 120 million? Assuming for simplicity’s sake that the investment was for a 100% ownership stake, all you need is a belief that achieving the trillion-dollar value has a probability of one-tenth of a percent for an expected return of over eight times your money. Who’s to say Etched doesn’t have that chance? And in that case, why would anyone not play? The foregoing is what I call “lottery-ticket thinking,” in which the dream of an enormous payoff justifies – no, compels – participation in an endeavor with an overwhelming probability of failing.

即使承认埃奇特(Etched)未必会成为有史以来最大的公司,但如果成功能使其估值达到英伟达(Nvidia)峰值的五分之一——也就是区区 1 万亿美元——那么需要多高的成功率才能证明投入 1.2 亿美元是合理的呢?为简化起见,假设这笔投资获得的是 100%的股权,你只需要相信实现万亿市值的概率达到千分之一,就能获得超过八倍的投资回报。谁又能断言埃奇特没有这样的机会呢?在这种情况下,又有什么理由不参与呢?我将上述思维方式称为“彩票思维”,即对巨额回报的幻想足以合理化——不,甚至迫使——参与一项失败概率极高的事业。

There’s nothing wrong with calculating expected values this way. Leading venture capitalists engage in it every day to great effect. But assumptions regarding the possible payoffs and their probabilities must be reasonable. Thinking about a trillion-dollar payout will override reasonableness in any calculation.

以这种方式计算预期价值本身并无问题。顶尖的风险投资家每天都在这样做,并取得了巨大成效。但对潜在回报及其概率的假设必须合理。一旦设想了万亿级别的回报,任何计算都将失去合理性。

Will AI produce profits, and for whom? Two things we know little or nothing about are the profits AI will produce for vendors and its impact on non-AI companies, primarily meaning those who employ it.

人工智能能否带来利润,以及谁将从中获益?我们目前对两件事几乎一无所知:一是人工智能将为供应商带来多少利润,二是它对非人工智能公司的影响,主要指那些使用人工智能的公司。

Will AI be a monopoly or duopoly, in which one or two leading companies are able to charge dearly for the capabilities? Or will it be a highly competitive free-for-all in which a number of firms compete on price for users’ spending on AI services, making it a commodity? Or, perhaps most likely, will it be a mix of leading companies and specialized players, some of whom compete on price and others through proprietary advantages. It’s said that the services currently responding to AI queries, such as ChatGPT and Gemini, lose money on every query they answer (of course, it’s not unusual for participants in a new industry to offer “loss leaders” for a while). Will the leading tech firms – used to success in winner-take-all markets – be content to experience losses in their AI businesses for years in order to gain share? Hundreds of billions of dollars are being committed to the race for AI leadership. Who will win, and what will be the result?

人工智能会形成垄断或双头垄断吗?即少数几家领先企业能够对其能力收取高昂费用?还是会出现高度竞争的自由市场局面,众多企业围绕用户在人工智能服务上的支出展开价格竞争,使人工智能变成一种商品?又或者,最有可能的情况是,市场将由几家龙头企业和一些专业玩家共同构成,其中部分企业通过价格竞争,另一些则依靠专有优势取胜。据称,目前响应人工智能查询的服务(如 ChatGPT 和 Gemini)每回答一次查询都会亏损(当然,在一个新兴产业中,参与者暂时提供“亏损引流”产品并不罕见)。那些长期习惯于赢者通吃市场的科技巨头,是否愿意为了抢占市场份额而多年忍受其人工智能业务的亏损?数百亿美元的资金正被投入这场人工智能领导权的争夺战。最终谁将胜出,结果又会如何?

Likewise, what will be AI’s impact on the companies that use it? Clearly, AI will be a great tool for enhancing users’ productivity by, among other things, replacing workers with computer-sourced labor and intelligence. But will this ability to cut costs add to the profit margins of the companies that employ it? Or will it simply enable price wars among those companies in the pursuit of customers? In that case, the savings might be passed on to the customers rather than garnered by the companies. In other words, is it possible AI will increase the efficiency of businesses without increasing their profitability? 同样,人工智能对使用它的企业会产生什么影响?显然,人工智能将是一种强大的工具,能够通过诸多方式提升用户的工作效率,例如用计算机生成的劳动力和智能取代人工。但这种降低成本的能力是否能提高采用它的企业的利润率?还是仅仅促使这些企业在争夺客户的过程中引发价格战?在这种情况下,节省下来的成本可能会转嫁给消费者,而非被企业自身获取。换句话说,人工智能是否可能提升企业的效率,却无法带来利润增长?

Should we worry about so-called “circular deals”? In the telecom boom of the late 1990s, in which optical fiber became overbuilt, fiber-owning companies engaged in transactions with each other that permitted them to report profits. If two companies own fiber, they just have an asset on their books. But if each buys capacity from the other, they can both report profits… so they did. In other cases, manufacturers loaned network operators money to buy equipment from them, before the operators had customers to justify the buildout. All this resulted in profits that were illusory.

我们是否应该担心所谓的“循环交易”?在 1990 年代末的电信热潮中,光纤网络过度建设,拥有光纤的公司之间相互进行交易,从而虚报利润。如果两家公司都拥有光纤,它们账面上只显示一项资产。但如果每家公司都从对方购买容量,双方都可以报告利润……于是它们就这么做了。在其他情况下,制造商向网络运营商贷款,让它们购买自己的设备,而这些运营商当时还没有客户来证明建设网络的合理性。所有这些行为最终导致了虚假的利润。

Nowadays, deals are being announced in which money appears to be round-tripped between AI players. People who believe there’s an AI bubble find it easy to view these transactions with suspicion. Is the purpose to achieve legitimate business goals or to exaggerate progress?

如今,一些交易被宣布,其中资金似乎在人工智能参与者之间来回流转。相信存在人工智能泡沫的人很容易对这些交易持怀疑态度:其目的究竟是实现合法的商业目标,还是为了夸大进展?

Adding to worries, critics say, some of the deals that OpenAI has made with chipmakers, cloud computing companies and others are oddly circular. OpenAI is set to receive billions from tech companies but also sends billions back to the same companies to pay for computing power and other services…

令人担忧的是,批评者指出,OpenAI 与芯片制造商、云计算公司及其他企业达成的一些交易显得颇为奇怪。OpenAI 将从科技公司获得数十亿美元,但同时也向同一家公司支付数十亿美元,用于支付计算能力和其他服务费用。

Nvidia has also made some deals that have raised questions about whether the company is paying itself. It announced that it would invest $100 billion in OpenAI. The start-up receives that money as it buys or leases Nvidia’s chips…

英伟达还达成了一些引发质疑的交易,人们怀疑该公司是否在为自己买单。该公司宣布将向 OpenAI 投资 1000 亿美元。这家初创企业获得这笔资金的方式,是通过购买或租赁英伟达的芯片……。

Goldman Sachs has estimated that Nvidia will make 15 percent of its sales next year from what critics also call circular deals. (The New York Times, November 20)

高盛估计,明年英伟达将有 15%的销售额来自批评者所称的“循环交易”。(《纽约时报》,2023 年 11 月)

Noteworthily, OpenAI has made investment commitments to industry counterparties totaling $1.4 trillion, even though it has yet to turn a profit. The company makes clear that the investments are to be paid out of revenues received from the same parties and that it has ways to back out of these commitments. But all this raises the question of whether the AI industry has developed a perpetual motion machine.

值得注意的是,尽管 OpenAI 尚未实现盈利,却已对行业合作伙伴做出了总计 1.4 万亿美元的投资承诺。该公司明确表示,这些投资将由来自相同合作方的收入支付,并且保留退出这些承诺的途径。但所有这一切都引发了疑问:人工智能行业是否已经形成了一种永动机制?

(On this subject, I’ve been enjoying articles questioning the ability of people to relate to the word “trillion,” and I think this idea is spot on. A million dollars is a dollar a second for 11.6 days. A billion dollars is a dollar a second for 31.7 years. We get that. But a trillion dollars is a dollar a second for 31,700 years. Who can get their head around the significance of 31,700 years?)

(关于这个话题,我一直在读一些文章,探讨人们是否能真正理解“万亿”这个词的含义,我认为这种观点非常准确。一百万美元相当于每秒一美元持续 11.6 天,十亿美元相当于每秒一美元持续 31.7 年,我们还能理解。但一万亿美元相当于每秒一美元持续 31,700 年。谁能真正理解 31,700 年的意义呢?)

What will be the useful life of AI assets? We have to wonder whether the topic of obsolescence is being handled correctly in AI-land. What will be the lifespan of AI chips? How many years of earnings growth should be counted on in assigning p/e ratios for AI-related stocks? Will chips and other aspects of AI infrastructure last long enough to repay the debt undertaken to buy them? Will artificial general intelligence (a machine capable of doing anything the human brain can do) be achieved? Will that be the end of progress, or might there be further revolutions, and what firms will win them? Will firms reach a position where technology is stable and they can extract economic value from it? Or will new technologies continually threaten to supplant older ones as the route to success?

人工智能资产的使用寿命将有多长?我们不得不质疑,在人工智能领域,过时问题是否得到了恰当处理。人工智能芯片的寿命会有多久?在为人工智能相关股票确定市盈率时,应预期多少年的盈利增长?芯片及其他人工智能基础设施能否维持足够长的时间,以偿还购买它们所承担的债务?通用人工智能(即能够完成人类大脑所能完成任何任务的机器)能否实现?这会是进步的终点,还是可能迎来进一步的革命?哪些企业将赢得这些变革?企业是否会达到技术趋于稳定的状态,从而能够从中获取经济价值?抑或新技术将持续威胁取代旧技术,成为通往成功的新路径?

In this connection, a single issue of an FT newsletter briefly mentioned two developments that suggest the fluid nature of the competitive landscape:

在此背景下,一份《金融时报》新闻简报曾简要提及两项发展,暗示了竞争格局的动态变化:

- A study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and open-source AI start-up Hugging Face found that the total share of downloads of new Chinese-made open models rose to 17 per cent in the past year. The figure surpasses the 15.8 per cent share of downloads from American developers such as Google, Meta and OpenAI – the first time Chinese groups have beaten their American counterparts…

麻省理工学院与开源人工智能初创公司 Hugging Face 的一项研究发现,过去一年中,新推出的中国自主研发开源模型的下载量占比已升至 17%。这一数字超过了谷歌、Meta 和 OpenAI 等美国开发者 15.8%的下载份额——这是中国团队首次在下载量上超越其美国对手。…… - Nvidia shares fell sharply yesterday on fears that Google is gaining ground in artificial intelligence, erasing $115bn in market value from the AI chipmaker. (FirstFT Americas, November 26)

由于担心谷歌在人工智能领域取得进展,英伟达股价昨日大幅下跌,导致这家人工智能芯片制造商市值蒸发 1150 亿美元。(FirstFT 美洲版,11 月 26 日)

Dynamic change creates the opportunity for incredible new technologies, but that same dynamism can threaten the leading companies’ reign. Amid all these uncertainties, investors must ask whether the assumption of continued success incorporated in the prices they’re paying is fully warranted.

动态变化为令人惊叹的新技术创造了机遇,但这种同样剧烈的变动也可能威胁到领先企业的统治地位。在所有这些不确定性之中,投资者必须思考:他们所支付的价格中所包含的持续成功假设,是否真正合理?

Is exuberance leading to speculative behavior? For an extreme example, I’ll cite the trend toward venture capital investments in startups via $1 billion “seed rounds.” Here’s one vignette:

过度乐观是否正导致投机行为?举个极端例子,我来谈谈当前初创企业通过“10 亿美元种子轮”进行风险投资的趋势。这里有一个小故事:

Thinking Machines, an AI startup helmed by former Open AI executive Mira Murati, just raised the largest seed round in history: 10 billion valuation. The company has not released a product and has refused to tell investors what they’re even trying to build. “It was the most absurd pitch meeting,” one investor who met with Murati said. “She was like, ‘So we’re doing an AI company with the best AI people, but we can’t answer any questions.’ ” (“The Is How the AI Bubble Will Pop,” Derek Thompson Substack, October 2)

由前 Open AI 高管米拉·穆拉蒂(Mira Murati)领导的人工智能初创公司 Thinking Machines 刚刚完成了历史上规模最大的一轮种子融资:获得 20 亿美元资金,估值达 100 亿美元。然而,该公司尚未推出任何产品,也拒绝向投资者透露他们究竟在开发什么。一位曾与穆拉蒂会面的投资者表示:“那场路演简直荒谬至极。她就像在说:‘我们正在打造一家由顶尖 AI 人才组成的公司,但对任何问题都无法作答。’”(德里克·汤普森,《AI 泡沫将如何破裂》,Substack,2023 年 10 月)

But that’s ancient history… already two months old. Here’s an update:

但那已经是陈年旧事了……已经过去两个月了。以下是最新更新:

Thinking Machines Lab, the artificial intelligence startup founded by former Open AI executive Mira Murati, is in early talks to raise a new funding round at a roughly 12 billion in July, after it raised about $2 billion. (Reuters, November 13)

据彭博社周四报道,由前 OpenAI 高管米拉·穆拉蒂创立的人工智能初创公司 Thinking Machines Lab,正在就新一轮融资进行早期洽谈,估值约为 500 亿美元。该公司上一次估值为 120 亿美元,是在今年 7 月完成约 20 亿美元融资之后。

And Thinking Machines Lab isn’t alone:

而 Thinking Machines Lab 并非孤例:

In one of the boldest bets yet in the AI arms race, Safe Superintelligence (SSI), the stealth startup founded by former OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever, has raised 32 billion – despite having no publicly released product or service. (CTech by Calcalist, April 13)

在人工智能军备竞赛中最具胆识的押注之一,是由前 OpenAI 首席科学家伊利亚·苏茨克弗创办的隐秘初创公司 Safe Superintelligence(SSI),已在此轮融资中募集了 20 亿美元,公司估值达到 320 亿美元——尽管该公司至今尚未推出任何公开的产品或服务。(Calcalist 旗下 CTech,4 月 13 日)

What’s the end state? Part of the issue with AI includes the unusual nature of this newest thing. This isn’t like a business that designs and sells a product, making money if the selling price exceeds the cost of the inputs. Rather, it’s companies building an airplane while it’s in flight, and once it’s built, they’ll know what it can do and whether anyone will pay for its services.

最终会走向何方?人工智能问题的一部分在于这种最新技术的特殊性质。这与传统企业设计并销售产品、当售价高于投入成本时就能盈利的情况完全不同。相反,这更像是企业在飞机飞行过程中建造它,只有等造好之后,才能知道它能做什么,以及是否有人愿意为其服务付费。

Many companies justify their spending because they’re not just building a product, they’re creating something that will change the world: artificial general intelligence, or A.G.I… The rub is that none of them quite know how to do it.

许多公司为其支出辩护的理由是,它们不仅仅在打造一款产品,更是在创造一种将改变世界的科技:通用人工智能(A.G.I.)。……然而问题在于,它们中没有一家真正清楚该如何实现这一点。

But Anton Korinek, an economist at the University of Virginia, said the spending would all be justified if Silicon Valley reached its goal. He is optimistic it can be done.

但弗吉尼亚大学的经济学家安东·科里内克表示,如果硅谷能够实现其目标,那么这些支出都将得到合理解释。他对此持乐观态度。

“It’s a bet on A.G.I. or bust,” Dr. Korinek said. (The New York Times, November 20 – emphasis added)

“这是一场对通用人工智能的豪赌,要么成功,要么失败,”科里内克博士说。(《纽约时报》,11 月 20 日——强调部分为原文所有)

The yet-to-be-determined nature of the industry under construction is best captured in remarks from Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, that have been paraphrased as follows: “we’ll build this sort of generally intelligent system and then ask it to figure out a way to generate an investment return from it.”

这一尚待确定的行业现状,最生动地体现在 OpenAI 首席执行官山姆·阿尔特曼的言论中,这些言论被概括为:“我们将构建这样一个具备普遍智能的系统,然后让它自己想办法从中获得投资回报。”

This should be a source of pause for people who heretofore fully comprehended the nature of the businesses they invested in. Clearly, the value of a technology that equals or surpasses the human brain should be pretty big, but isn’t it well beyond calculation?

对于那些此前完全理解自己所投资企业性质的人来说,这应该是一个值得深思的警示。显然,一种能够等于甚至超越人脑的技术的价值应该非常巨大,但难道它不已经远远超出计算范围了吗?

A Word About the Use of Debt

To date, much of the investment in AI and the supporting infrastructure has consisted of equity capital derived from operating cash flow. But now, companies are committing amounts that require debt financing, and for some of those companies, the investments and leverage have to be described as aggressive.

到目前为止,人工智能及其支撑基础设施的大部分投资都来自运营现金流产生的股权资本。但如今,企业正在投入需要债务融资的巨额资金,而对于其中一些公司而言,这些投资和杠杆水平必须被描述为激进的。

The AI data centre boom was never going to be financed with cash alone. The project is too big to be paid for out of pocket. JPMorgan analysts have done some sums on the back of a napkin, or possibly a tablecloth, and estimated the bill for the infrastructure build-out would come to 350bn in the bank, collectively, as of the end of the third quarter. (“Unhedged,” Financial Times, November 13)

人工智能数据中心的繁荣不可能仅靠现金来支撑。这个项目规模太大,无法用自有资金支付。摩根大通的分析师在餐巾纸甚至可能是桌布上粗略计算了一下,估计基础设施建设的成本将达到 5 万亿美元(还不包括小费)。虽然没人知道这个数字是否准确,但我们有充分理由预计明年将有接近半万亿美元的支出。与此同时,最大的几个投资者(微软、谷歌、亚马逊、Meta 和甲骨文)截至第三季度末,合计只有约 3500 亿美元的现金储备。(《未对冲》,《金融时报》,11 月 13 日)

The firms mentioned above derive healthy cash flows from their very strong non-AI businesses. But the massive, winner-take-all arms race in AI is requiring some to take on debt. In fact, it’s reasonable to think one of the reasons they’re spending vast sums is to make it hard for lesser firms to keep up.

上述企业依靠其强劲的非人工智能业务产生了健康的现金流。然而,人工智能领域这场规模巨大、赢家通吃的军备竞赛,迫使一些企业不得不举债。事实上,可以合理推测,它们投入巨资的部分原因正是为了使实力较弱的企业难以跟上步伐。

Oracle, Meta, and Alphabet have issued 30-year bonds to finance AI investments. In the case of the latter two, the yields on the bonds exceed those on Treasurys of like maturity by 100 basis points or less. Is it prudent to accept 30 years of technological uncertainty to make a fixed-income investment that yields little more than riskless debt? And will the investments funded with debt – in chips and data centers – maintain their level of productivity long enough for these 30-year obligations to be repaid?

甲骨文、Meta 和谷歌母公司阿尔法贝特已发行 30 年期债券以资助人工智能投资。就后两者而言,其债券收益率仅比同期国债高出 100 个基点或更少。为了获得一个仅略高于无风险债务收益的固定收益投资,承担长达 30 年的技术不确定性是否明智?而这些由债务融资所支持的投资——芯片和数据中心——能否保持足够长时期的生产力,以偿还这 30 年的债务义务?

On November 14, Alex Kantrowitz’s Big Technology Podcast carried a conversation with Gil Luria, Head of Technology Research at financial services firm D.A. Davidson, primarily regarding the use of debt in the AI sector. Here’s some of what Luria had to say:

11 月 14 日,亚历克斯·坎特罗维茨的《大科技播客》中,采访了金融服务公司 D.A.戴维森的技术研究主管吉尔·卢里亚,主要讨论了人工智能领域使用债务的问题。以下是卢里亚的部分发言内容:

- Healthy behavior is being practiced by “… reasonable, thoughtful business leaders, like the ones at Microsoft, Amazon, and Google that are making sound investments in growing the capacity to deliver AI. And the reason they can make sound investments is that they have all the customers… And so, when they make investments, they’re using cash on their balance sheets; they have tremendous cash flow to back it up; they understand that it’s a risky investment; and they balance it out.”

“合理的、深思熟虑的企业领导者,比如微软、亚马逊和谷歌的那些人,正在践行健康的行为,他们正稳健地投资于提升人工智能交付能力。他们之所以能够做出稳健的投资,是因为他们拥有全部客户……因此,当他们进行投资时,使用的是资产负债表上的现金;他们有强大的现金流作为支撑;他们清楚这是一项高风险投资,并且会加以权衡。” - Unhealthy behavior – Here he describes “… a startup that is borrowing money to build data centers for another startup. They’re both losing tremendous amounts of cash, and yet they’re somehow being able to raise this debt capital in order to fund this buildout, again without having the customers or the visibility into those investments paying off.”

不健康的行为——他这里描述道:“… 有一家初创公司正在借钱建设数据中心,而这笔资金是用来支持另一家初创公司的。 双方都在严重亏损,却仍能以某种方式筹集到债务资本,用于支持这项扩建,而且他们根本没有客户,也无法预见这些投资会带来回报。 ” - “So there’s a whole range of behaviors between healthy and unhealthy, and we just need to sort that out so we don’t make the mistakes of the past.”

“在健康与不健康之间存在着一系列的行为模式,我们只需要理清这些差异,以免重蹈过去的错误。” - “There are certain things we finance through equity, through ownership, and there are certain things we finance through debt, through an obligation to pay down interest over time. And as a society, for the longest time, we’ve had those two pieces in their right place. Debt is when I have a predictable cash flow and/or an asset that can back that loan, and then it makes sense for me to exchange capital now for future cash flows to the lender… We use equity for investing in more speculative things, for when we want to grow and we want to own that growth, but we’re not sure about what the cash flow is going to be. That’s how a normal economy functions. When you start confusing the two you get yourself in trouble.”

我们通过股权、通过所有权来融资某些项目,而另一些项目则通过债务、通过偿还利息的义务来融资。作为社会整体而言,长期以来,这两者一直保持在恰当的位置上。当我的现金流可预测,或拥有能够支撑贷款的资产时,就适合使用债务;这时,我用现在的资本换取未来对贷款人的现金流回报,是合理的……我们用股权来投资更具投机性的项目,即当我们希望实现增长并拥有这种增长时,但又不确定未来的现金流会如何。这就是正常经济运行的方式。一旦你混淆了这两者,就会给自己带来麻烦。

Among potentially worrisome factors, Luria cites these:

在可能令人担忧的因素中,卢里亚提到了以下几点:

- “A speculative asset… we don’t know how much of it we’re really going to need in two to five years.”

“一种投机性资产……我们并不清楚两到五年后真正需要多少。” - Lender personnel with incentives to make loans but no exposure to long-term consequences

激励贷款人员发放贷款,却无需承担长期后果 - The possibility that the supply of AI capacity catches up with or surpasses the demand

人工智能算力供应与需求相匹配甚至超过需求的可能性 - The chance that future generations of AI chips will be more powerful, obsoleting existing ones or reducing their value as backing for debt

下一代人工智能芯片可能更强大,从而淘汰现有芯片或降低其作为债务担保的价值的可能性 - Powerful competitors who vie for market share by cutting rental rates and running losses

通过降低租金费率和持续亏损来争夺市场份额的强大竞争对手

Here are some important paragraphs from Azeem Azhar’s Exponential View of October 18:

以下是阿齐姆·阿扎尔 2023 年 10 月 18 日《指数视野》中的几段重要内容:

When does an AI boom tip into a bubble? [Investor and engineer] Paul Kedrosky points to the Minsky moment – the inflection point when credit expansion exhausts its good projects and starts chasing bad ones, funding marginal deals with vendor financing and questionable coverage ratios. For AI infrastructure, that shift may already be underway; the telltale signs include hyperscalers’ capex outpacing revenue momentum and lenders sweetening terms to keep the party alive.

人工智能热潮何时会演变为泡沫?[投资者兼工程师]保罗·凯德罗斯基指出,这正是明斯基时刻——当信贷扩张耗尽优质项目,开始追逐劣质项目之时,资金转向供应商融资和可疑的覆盖率比率,以支撑边缘性交易。对于人工智能基础设施而言,这种转变可能已经悄然发生;明显的迹象包括超大规模企业资本支出增速超过收入增长势头,以及贷款方不断放宽条款,以维持这场繁荣。

Paul makes a compelling case. We’ve entered speculative finance territory – arguably past the tentative stage – and recent deals will set dangerous precedents. As Paul warns, this financing will “create templates for future such transactions,” spurring rapid expansion in junk issuance and SPV proliferation among hyperscalers chasing dominance at any cost…

保罗的论点极具说服力。我们已进入投机性金融的领域——甚至可以说已越过试探阶段——近期的交易将树立危险的先例。正如保罗所警告的,此类融资将“为未来类似交易建立模板”,从而推动垃圾债发行量迅速增长,并促使超大规模企业为争夺主导地位不计成本地大量设立特殊目的实体(SPV)……

For AI infrastructure, the warning signs are flashing: vendor financing proliferates, coverage ratios thin, and hyperscalers leverage balance sheets to maintain capex velocity even as revenue momentum lags. We see both sides – genuine infrastructure expansion alongside financing gymnastics that recall the 2000 telecom bust. The boom may yet prove productive, but only if revenue catches up before credit tightens. When does healthy strain become systemic risk? That’s the question we must answer before the market does. (Emphasis added)

对于人工智能基础设施而言,警示信号正在闪烁:供应商融资泛滥、覆盖比率下降,而超大规模云服务商即使收入增长放缓,仍利用资产负债表维持资本支出的高速度。我们看到了两面:真实的基础设施扩张,以及令人联想到 2000 年电信业崩盘的融资操作。繁荣或许仍能带来实际产出,但前提是收入能在信贷收紧前跟上步伐。当健康的压力演变为系统性风险时,就是我们必须在市场之前回答的问题。(强调部分已标注)

Azhar references the use of off-balance sheet financing via special-purpose vehicles, or SPVs, which were among the biggest contributors to Enron’s precariousness and eventual collapse. A company and its partners set up an SPV for some specific purpose(s) and supply the equity capital. The parent company may have operating control, but because it doesn’t have majority ownership, it doesn’t consolidate the SPV on its financial statements. The SPV takes on debt, but that debt doesn’t appear on the parent’s books. The parent may be an investment grade borrower, but likewise, the debt isn’t an obligation of the parent or guaranteed by it. Today’s debt may be backed by promised rent from a data center tenant – sometimes an equity partner – but the debt isn’t a direct obligation of the equity partner either. Essentially, an SPV is a way to make it look like a company isn’t doing the things the SPV is doing and doesn’t have the debt the SPV does. (Private equity funds and private credit funds are highly likely to be found among the partners and lenders in these entities.)

阿扎尔提到了通过特殊目的实体(SPV)进行表外融资的使用,这正是导致安然陷入困境并最终崩溃的主要因素之一。公司及其合作伙伴为某个特定目的设立一个 SPV,并提供股权资本。母公司可能拥有运营控制权,但由于不拥有多数股权,因此不会将 SPV 纳入其财务报表合并范围。SPV 承担债务,但这些债务不会出现在母公司的账簿上。母公司可能是投资级借款人,但同样,这些债务并非母公司的义务,也不由其担保。如今的债务可能由数据中心租户承诺支付的租金作为支撑——有时该租户也是股权合作伙伴——但这些债务同样不是股权合作伙伴的直接责任。本质上,SPV 是一种让公司看起来并未从事 SPV 所开展的业务,也未承担 SPV 所背负债务的方式。(私募股权基金和私募信贷基金极有可能是此类实体中的合作伙伴和贷款方。)

As I quoted earlier, according to Perez (who wrote on the heels of the dot-com bubble), “what enabled the deployment period were the money-losing investments.” Early investment is lost in the “Minsky moment,” in which unwise commitments made in an extended up-cycle encounters value destruction in a correction. And there are three things we know for sure about the use of debt:

正如我之前引用的那样,根据佩雷兹(她在网络泡沫之后撰文)的观点,“推动部署期的是那些亏损的投资。”早期投资在“明斯基时刻”中损失殆尽,即在长期上升周期中做出的不明智承诺,在市场回调时遭遇价值毁灭。关于债务的使用,我们有三点是确定无疑的:

- it magnifies losses if there are losses (just as it magnifies the hoped-for gains if they materialize),

它会放大亏损(就像它会放大预期收益的实现一样), - it increases the probability of a venture failing if it encounters a difficult moment, and

一旦遇到困难时刻,会增加项目失败的概率,而且 - despite the layer of equity beneath it, it puts lenders’ capital at risk if the difficult moment is bad enough.

尽管其下方有股权层作为缓冲,但如果困难时刻足够严重,仍会使贷款人的资本面临风险。

One key risk to consider is the possibility that the boom in data center construction will result in a glut. Some data centers may be rendered uneconomic, and some owners may go bankrupt. In that case, a new generation of owners might buy up centers at pennies on the dollar from lenders who foreclosed on them, reaping profits when the industry stabilizes. This is a process through which “creative destruction” brings markets into equilibrium and reduces costs to levels that make future business profitable.

一个需要考虑的关键风险是,数据中心建设的繁荣可能导致产能过剩。部分数据中心可能变得无利可图,一些所有者甚至可能破产。在这种情况下,新一代的所有者或许能以极低的价格从被迫清算的贷款人手中收购这些数据中心,在行业稳定后获得利润。这一过程正是“创造性破坏”推动市场回归均衡、并将成本降至足以使未来业务盈利水平的体现。

Debt is neither a good thing nor a bad thing per se. Likewise, the use of leverage in the AI industry shouldn’t be applauded or feared. It all comes down to the proportion of debt in the capital structure; the quality of the assets or cash flows you’re lending against; the borrowers’ alternative sources of liquidity for repayment; and the adequacy of the safety margin obtained by lenders. We’ll see which lenders maintain discipline in today’s heady environment.

债务本身既非好事也非坏事。同样地,人工智能行业使用杠杆也不应被歌颂或恐惧。关键在于资本结构中债务的比例;你所抵押的资产或现金流的质量;借款人偿还债务的其他流动性来源;以及贷款人获得的安全边际是否充足。在当前狂热的环境中,我们将看到哪些贷款人能保持纪律。

It’s worth noting in this connection that Oaktree has made a few investments in data centers, and our parent, Brookfield, is raising a $10 billion fund for investment in AI infrastructure. Brookfield is putting up its own money and has equity commitments from sovereign wealth funds and Nvidia, to which it intends to apply “prudent” debt. Brookfield’s investments seem likely to go largely into geographies that are less saturated with data centers and for infrastructure to supply the vast amounts of electric power that data centers will require. Of course, we’re both doing these things on the basis of what we think are prudent decisions.

需要指出的是,橡树资本已对数据中心进行了一些投资,而我们的母公司布鲁克菲尔德正在募集一支 100 亿美元的基金,用于投资人工智能基础设施。布鲁克菲尔德将投入自有资金,并已获得主权财富基金及英伟达的股权承诺,计划对其投资应用“审慎”的债务。布鲁克菲尔德的投资似乎主要会投向数据中心尚未过度饱和的地区,以及为数据中心所需大量电力供应的基础设施。当然,我们双方都是基于我们认为审慎的决策来开展这些事情。

I know I don’t know enough to opine on AI. But I do know something about debt, and it’s this:

我知道自己对人工智能了解得还不够多,无法发表意见。但我对债务却有些了解,那就是:

- It’s okay to supply debt financing for a venture where the outcome is uncertain.

为结果不确定的项目提供债务融资是可以接受的。 - It’s not okay where the outcome is purely a matter of conjecture.

当结果纯粹取决于猜测时,这种情况是不可接受的。 - Those who understand the difference still have to make the distinction correctly.

即使理解两者区别的那些人,仍必须正确地做出区分。

The FT’s Unhedged quotes Chong Sin, lead analyst for CMBS research at JPMorgan, as saying, “… in our conversations with investment grade ABS and CMBS investors, one often-cited concern is whether they want to take on the residual value risk of data centers when the bonds mature.” I’m glad potential lenders are asking the kind of questions they should.

《金融时报》未加掩饰地引用了摩根大通 CMBS 研究主管钟申的话:“……在与投资级 ABS 和 CMBS 投资者的交流中,一个常被提及的担忧是,他们是否愿意在债券到期时承担数据中心的剩余价值风险。”我很高兴潜在贷款人正在提出他们本应提出的问题。

Here’s how to think about the intersection of debt and AI according to Bob O’Leary, Oaktree’s co-CEO and co-portfolio manager of our Opportunities Funds:

以下是根据橡树资本联合首席执行官兼我们机会基金联合投资组合经理鲍勃·奥利里(Bob O’Leary)的观点,如何思考债务与人工智能交汇之处:

Most technological advances develop into winner-takes-all or winner-takes-most competitions. The “right” way to play this dynamic is through equity, not debt. Assuming you can diversify your equity exposures so as to include the eventual winner, the massive gain from the winner will more than compensate for the capital impairment on the losers. That’s the venture capitalist’s time-honored formula for success.

大多数技术进步都会演变为“赢家通吃”或“赢家大吃”的竞争格局。在这种动态中,正确的玩法是通过股权而非债务。假设你能够分散你的股权投资,从而涵盖最终的胜出者,那么胜出者带来的巨大收益将足以弥补其他失败者的资本损失。这就是风险投资家长期以来成功的核心公式。

The precise opposite is true of a diversified pool of debt exposures. You’ll only make your coupon on the winner, and that will be grossly insufficient to compensate for the impairments you’ll experience on the debt of the losers.

与之完全相反的是,多元化债务投资组合的情况。你只能从胜出者那里获得票息收入,而这远远不足以弥补你在失败者债务上遭受的损失。

Of course, if you can’t identify the pool of companies from which the winner will emerge, the difference between debt and equity is irrelevant – you’re a zero either way. I mention this because that’s precisely what happened in search and social media: early leaders (Lycos in search and MySpace in social media) lost out spectacularly to companies that emerged later (Google in search and Facebook in social media).

当然,如果你无法识别出最终胜出的企业群体,那么债权与股权的区别就毫无意义——无论选择哪种方式,结果都是零。我之所以提到这一点,是因为这正是搜索引擎和社交媒体领域发生的情况:早期的领先者(搜索领域的 Lycos、社交媒体领域的 MySpace)惨败于后来崛起的企业(搜索领域的 Google、社交媒体领域的 Facebook)。

Trying to Get to a Conclusion

There can be no doubt that today’s behavior is “speculative,” defined as based on speculation regarding the future. There’s also no doubt that no one knows what the future holds, but investors are betting huge sums on that future.

毫无疑问,如今的行为是“投机性的”,即基于对未来情况的猜测。同样毫无疑问的是,没有人知道未来会怎样,但投资者却在巨额押注于未来。

In that connection, I want to say a little about the unique nature of AI. The AI revolution is different from the technological revolutions that preceded it in ways that are both wonderful and worrisome. It feels to me like a genie has been released from a bottle, and it isn’t going back in:

在这方面,我想简要谈谈人工智能的独特性质。人工智能革命与此前所有的技术革命都不同,这种差异既令人欣喜,又令人担忧。在我看来,这就像一个精灵从瓶中被释放出来,再也无法收回:

AI may not be a tool for mankind, but rather something of a replacement. It may be capable of taking over cognition, on which humans have thus far had a monopoly. Because of this, it’s likely to be different in kind from prior developments, not just in degree. (More on this in my postscript.)

人工智能可能不再是人类的工具,而更像是一种替代品。它或许有能力接管认知功能,而这一能力此前一直是人类独有的。正因为如此,它在本质上将不同于以往的发展,而不仅仅是程度上的差异。(更多内容请见我的附录。)

AI technology is progressing at an incredibly rapid clip, possibly leaving scant time for mankind to adjust. I’ll provide two examples:

人工智能技术正以极其迅猛的速度发展,可能留给人类适应的时间所剩无几。我将举两个例子:

- Coding, which we called “computer programming” 60 years ago, is the canary in the coal mine in terms of the impact of AI. In many advanced software teams, developers no longer write the code; they type in what they want, and AI systems generate the code for them. Coding performed by AI is at a world-class level, something that wasn’t so just a year ago. According to my guide here, “There is no speculation about whether or not human replacement will take place in that vertical.”

编码,六十年前我们称之为“计算机编程”,如今在人工智能影响下犹如煤矿中的金丝雀。在许多先进的软件团队中,开发者已不再亲自编写代码;他们只需输入自己的需求,由 AI 系统自动生成代码。如今由人工智能完成的编码已达到世界级水平,而这一情况在一年前还并不存在。据我这里的向导所说:“在这一领域,人类是否会被取代已无任何争议。” - In the field of digital advertising, when users log into an app, AI engages in “ad matching,” showing them ads tailored to the preferences displayed by their prior surfing. No humans need apply to do this job.

在数字广告领域,当用户登录应用程序时,人工智能会进行“广告匹配”,根据用户此前浏览行为所表现出的偏好,向其展示量身定制的广告。这项工作无需人类参与。

Perhaps most importantly, the growth of demand for AI seems totally unpredictable. As one of my younger advisers explained, “the speed and scale of improvement mean it’s incredibly hard to forecast demand for AI. Adoption today may have nothing to do with adoption tomorrow, because a year or two from now, AI may be able to do 10x or 100x what it can do today. Thus, how can anyone say how many data centers will be needed? And how can even successful companies know how much computing capacity to contract for?”

也许最重要的是,对人工智能需求的增长似乎完全难以预测。正如我一位年轻的顾问所解释的:“进步的速度和规模意味着,预测人工智能的需求极其困难。今天的采用情况可能与明天毫无关系,因为一两年后,人工智能的能力可能会比现在提升 10 倍甚至 100 倍。因此,谁又能说清楚需要多少数据中心呢?即使是成功的企业,又如何知道应预订多少计算能力?”

With differences like these, how can anyone correctly judge what AI implies for the future?

存在这些差异,人们又如何能正确判断人工智能对未来意味着什么?

* * *

One of the things occupying many observers at this juncture – including me – is the search for parallels to past bubbles. Here’s some historical perspective from a recent article in Wired:

此时此刻,许多观察者(包括我自己)都在关注过去泡沫的相似之处。以下是《连线》杂志最近一篇文章提供的历史视角:

AI’s closest historical analogue here may be not electric lighting but radio. When RCA started broadcasting in 1919, it was immediately clear that it had a powerful information technology on its hands. But less clear was how that would translate into business. “Would radio be a loss-leading marketing for department stores? A public service for broadcasting Sunday sermons? An ad-supported medium for entertainment?” [Brent Goldfarb and David A. Kirsch of the University of Maryland] write. “All were possible. All were subjects of technological narratives.” As a result, radio turned into one of the biggest bubbles in history – peaking in 1929, before losing 97 percent of its value in the crash. This wasn’t an incidental sector; RCA was, along with Ford Motor Company, the most high-traded stock on the market. It was, as The New Yorker recently wrote, “the Nvidia of its day.”…

在这里,人工智能最接近的历史类比或许不是电灯,而是无线电。当美国无线电公司(RCA)于 1919 年开始广播时,人们立刻意识到自己掌握了一项强大的信息科技。但这种技术如何转化为商业价值却并不清晰。“无线电会不会成为百货公司的一种引流营销手段?会不会成为播放星期日布道的公共服务?会不会成为以广告支持的娱乐媒介?”马里兰大学的布伦特·戈德法布(Brent Goldfarb)和大卫·A·基尔希(David A. Kirsch)写道,“所有这些可能性都存在,也都成为技术叙事的主题。”结果,无线电演变成了历史上最大的泡沫之一——在 1929 年达到顶峰,随后在大崩盘中市值蒸发了 97%。这并非偶然的行业;RCA 与福特汽车公司一样,是当时市场上交易最活跃的股票之一。正如《纽约客》最近所写:“它就是那个时代的英伟达。”……

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris… It was the biggest tech demo of the day, and it became an enormous, ChatGPT-launch-level coordinating event – a signal to investors to pour money into the industry.

1927 年,查尔斯·林德伯格完成了从纽约到巴黎的首次单人不间断跨大西洋飞行……这是当时最重大的技术演示,也成为了一场规模堪比 ChatGPT 发布的重要协调事件——向投资者发出信号,将资金投入这一行业。

“Expert investors appreciated correctly the importance of airplanes and air travel,” Goldfarb and Kirsch write, but “the narrative of inevitability largely drowned out their caution. Technological uncertainty was framed as opportunity, not risk. The market overestimated how quickly the industry would achieve technological viability and profitability.”

“专家投资者正确地认识到飞机和航空旅行的重要性,”戈德法布和基尔施写道,但“不可避免性的叙事在很大程度上淹没了他们的谨慎。技术上的不确定性被视作机遇,而非风险。市场高估了该行业实现技术可行性和盈利的速度。”

As a result, the bubble burst in 1929 – from its peak in May, aviation stocks dropped 96 percent by May 1932…

结果,泡沫于 1929 年破裂——从 5 月的峰值算起,到 1932 年 5 月,航空股票下跌了 96%。……

It’s worth reiterating that two of the closest analogs AI seems to have in tech bubble history are aviation and broadcast radio. Both were wrapped in high degrees of uncertainty and both were hyped with incredibly powerful coordinating narratives. Both were seized on by pure play companies seeking to capitalize on the new game-changing tech, and both were accessible to the retail investors of the day. Both helped inflate a bubble so big that when it burst, in 1929, it left us with the Great Depression. (“AI Is the Bubble to Burst Them All,” Brian Merchant, Wired, October 27 – emphasis added. N.b., the Depression had many causes beyond the bursting of the radio/aviation bubble.)

值得重申的是,人工智能在科技泡沫历史中最为接近的两个类比是航空业和广播无线电。两者都笼罩在高度不确定性之中,且都被极具影响力的统一叙事所炒作。两者都吸引了纯粹专注于该领域的公司,试图利用这项颠覆性新技术牟利,也都对当时的散户投资者开放。两者共同推高了一个巨大的泡沫,当它在 1929 年破裂时,导致了大萧条的出现。(“人工智能是将一切泡沫一网打尽的那一个”,布莱恩·默切特,《连线》杂志,10 月 27 日——强调部分为原文所有。注意:大萧条的发生原因远不止广播/航空泡沫破裂这一项。)

Derek Thompson, who supplied the quote with which I opened this memo, ended his newsletter with some terrific historical perspective:

达里尔·汤普森,正是他为本备忘录提供了开篇引言,他在自己的通讯结尾给出了极为精彩的历史视角:

The railroads were a bubble and they transformed America. Electricity was a bubble, and it transformed America. The broadband build-out of the late-1990s was a bubble that transformed America. I am not rooting for a bubble, and quite the contrary, I hope that the US economy doesn’t experience another recession for many years. But given the amount of debt now flowing into AI data center construction, I think it’s unlikely that AI will be the first transformative technology that isn’t overbuilt and doesn’t incur a brief painful correction. (“AI Could Be the Railroad of the 21 st Century. Brace Yourself.” November 4 – emphasis added)

铁路曾是一场泡沫,却彻底改变了美国。电力曾是一场泡沫,也彻底改变了美国。上世纪 90 年代末的宽带建设热潮是一场泡沫,同样彻底改变了美国。我并不希望出现泡沫,恰恰相反,我希望美国经济在未来许多年内都不会经历另一次衰退。但鉴于目前大量债务正涌入人工智能数据中心的建设,我认为人工智能很可能是首个不会过度建设、也不会经历短暂痛苦调整的变革性技术。 (“人工智能可能是 21 世纪的铁路。做好准备吧。” 11 月 4 日 – 强调部分为原文所有)

The skeptics readily cite ways in which today’s events are comparable to the internet bubble:

怀疑者们很容易指出,当下的情况与互联网泡沫时期有许多相似之处:

- A change-the-world technology

- Exuberant, speculative behavior

- The role of FOMO

- Suspect, circular deals

- The use of SPVs

- $1 billion seed rounds

The supporters have reasons why the comparison isn’t appropriate:

支持者则有理由认为这种类比并不恰当:

- An existing product for which there is strong demand

一款已有强劲需求的产品 - One billion users already (many times the number of internet users at the height of the bubble)

已有一亿用户(远超泡沫高峰期的互联网用户数量) - Well-established main players with revenues, profits, and cash flow

拥有稳定营收、利润和现金流的主流企业 - The absence of an IPO craze with prices doubling in a day

没有 IPO 狂热,股价不会一天翻倍 - Reasonable p/e ratios for the established participants

成熟参与者的合理市盈率

I’ll elaborate regarding the first of the proposed non-comparable factors. Unlike in the internet bubble, AI products already exist at scale, the demand for them is exploding, and they’re producing revenues in rapidly increasing amounts. For example, Anthropic, one of the two leaders in producing models for AI coding as described on page 12, is said to have “10x-ed” its revenues in each of the last two years (for those who didn’t study higher math, that’s 100x in two years). Revenues from Claude Code, a program for coding that Anthropic introduced earlier this year, already are said to be running at an annual rate of 1 million in 2023 and 1 billion this year.

我将详细说明所提出的不可比因素中的第一个。与互联网泡沫不同,人工智能产品目前已大规模存在,其需求正在急剧增长,并且收入正以迅速增加的幅度产生。例如,根据第 12 页所述,作为人工智能编程模型两大领导者之一的 Anthropic 公司,据称在过去两年中收入实现了“10 倍”增长(对那些没有学过高数的人来说,这意味着两年内增长了 100 倍)。Anthropic 今年早些时候推出的编程工具 Claude Code 的收入,据称已达到每年 10 亿美元的水平。另一大领导者 Cursor 的收入在 2023 年为 100 万美元,2024 年达到 1 亿美元,同样预计今年将达到 10 亿美元。

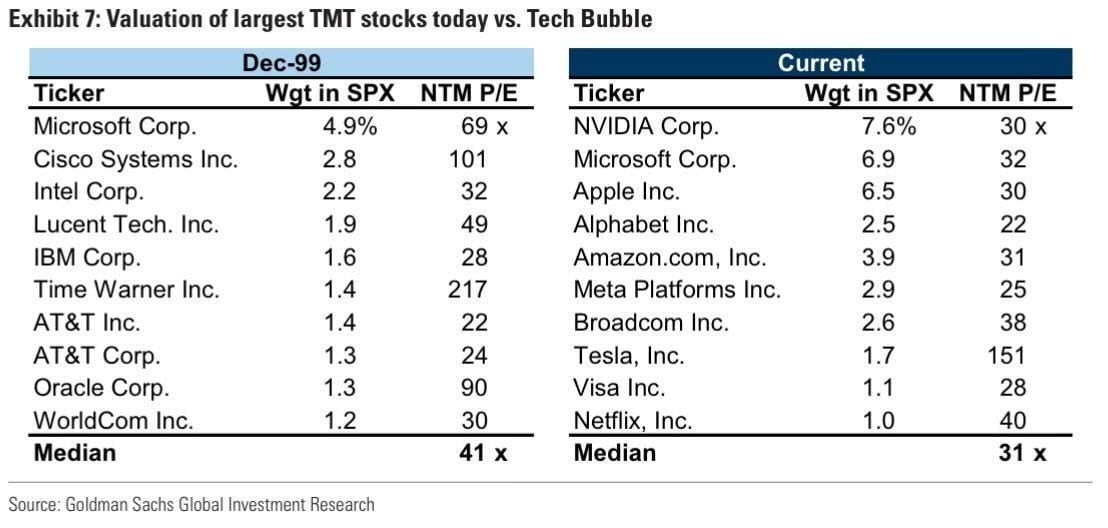

As to the final bullet point, see the table below, which comes from Goldman Sachs via Derek Thompson. You’ll notice that during the internet bubble of 1998-2000, the p/e ratios were much higher for Microsoft, Cisco, and Oracle than they are today for the biggest AI players – Nvidia, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta (OpenAI doesn’t have earnings). In fact, Microsoft’s on a half-off sale relative to its p/e 26 years ago! In the first bubble I witnessed – surrounding the Nifty-Fifty in 1969-72 – the p/e ratios for the leading companies were even higher than those of 1998-2000.

至于最后一个要点,请参见下表,数据来自高盛公司,经德里克·汤普森转述。您会注意到,在 1998-2000 年的互联网泡沫期间,微软、思科和甲骨文的市盈率远高于如今最大 AI 企业——英伟达、微软、谷歌母公司阿尔法贝特、亚马逊和 Meta(OpenAI 无盈利数据)的市盈率。事实上,微软当前的市盈率相比 26 年前已打对折!在我亲历的第一个泡沫——1969-72 年围绕“漂亮 50”股票的泡沫——中,领先公司的市盈率甚至比 1998-2000 年还要高。

In Conclusion

For my final citation, I’ll look to Sam Altman of OpenAI. His comments seem to me to capture the essence of what’s going on:

在最后的引用中,我将参考 OpenAI 的山姆·阿尔特曼。在我看来,他的言论准确地捕捉到了当前局势的本质:

“When bubbles happen, smart people get overexcited about a kernel of truth,” Mr. Altman told reporters this year. “Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about A.I.? My opinion is yes. Is A.I. the most important thing to happen in a very long time? My opinion is also yes.” (The New York Times, November 20)

“当泡沫出现时,聪明人会对一个事实的种子过度兴奋,”今年阿爾特曼先生对记者说。“我们是否正处于投资者整体对人工智能过度兴奋的阶段?我的看法是肯定的。人工智能是否是很久以来最重要的事情?我的看法也是肯定的。”(《纽约时报》,2023 年 11 月)

But do I have a bottom line? Yes, I do. Alan Greenspan’s phrase, mentioned earlier, serves as an excellent way to sum up a stock market bubble: “irrational exuberance.” There is no doubt that investors are applying exuberance with regard to AI. The question is whether it’s irrational. Given the vast potential of AI but also the large number of enormous unknowns, I think virtually no one can say for sure. We can theorize about whether the current enthusiasm is excessive, but we won’t know until years from now whether it was. Bubbles are best identified in retrospect.

但我有底线吗?有,我有。之前提到的艾伦·格林斯潘的表述,恰好可以用来概括股市泡沫:“非理性繁荣”。毫无疑问,投资者对人工智能确实表现出过度的热情。问题是,这种热情是否非理性。鉴于人工智能的巨大潜力,同时也存在大量难以预知的未知因素,我认为几乎没有人能确信地回答。我们可以推测当前的热情是否过度,但只有等到多年以后才能知道答案。泡沫往往只能在事后才能被识别。

While the parallels to past bubbles are inescapable, believers in the technology will argue that “this time it’s different.” Those four words are heard in virtually every bubble, explaining why the present situation isn’t a bubble, unlike the analogous prior ones. On the other hand, Sir John Templeton, who in 1987 drew my attention to those four words, was quick to point out that 20% of the time things really are different. But on the third hand, it must be borne in mind that behavior based on the belief that it’s different is what causes it to not be different!

尽管与以往泡沫的相似之处显而易见,但技术信仰者仍会辩称“这次不一样”。这四个字几乎在每一轮泡沫中都会被听到,用来解释为何当前的情况并非泡沫,而不同于以往的类似情形。另一方面,1987 年曾提醒我注意这四个字的约翰·坦普尔顿爵士很快指出,有 20%的情况下事情确实不同。但再进一步说,必须牢记:正是基于“情况不同”这一信念所采取的行为,恰恰导致了它其实并无不同!

Today’s situation calls to mind a comment attributed to American economist Stuart Chase about faith. I believe it’s also applicable to AI (as well as to gold and cryptocurrencies):

当下的局面让我想起美国经济学家斯图尔特·切斯关于信念的一句评述。我认为这句话同样适用于人工智能(也适用于黄金和加密货币):

For those who believe, no proof is necessary. For those who don’t believe, no proof is possible. 对相信的人而言,无需证明;对不相信的人而言,任何证明都无可能。

Here’s my actual bottom line:

这就是我真正的结论:

- There’s a consistent history of transformational technologies generating excessive enthusiasm and investment, resulting in more infrastructure than is needed and asset prices that prove to have been too high. The excesses accelerate the adoption of the technology in a way that wouldn’t occur in their absence. The common word for these excesses is “bubbles.”

历史上,具有变革性意义的技术总是引发过度的热情与投资,导致基础设施过剩,资产价格也最终被证明过高。这些过度现象会以一种在没有它们的情况下不会出现的方式,加速技术的普及。人们通常将这种过度现象称为“泡沫”。 - AI has the potential to be one of the greatest transformational technologies of all time.

人工智能有可能成为有史以来最具变革性的技术之一。 - As I wrote just above, AI is currently the subject of great enthusiasm. If that enthusiasm doesn’t produce a bubble conforming to the historical pattern, that will be a first.

正如我刚才所写,目前人工智能正受到极大的追捧。如果这种热情没有产生符合历史模式的泡沫,那将是前所未有的第一次。 - Bubbles created in this process usually end in losses for those who fuel them.

在这种过程中形成的泡沫,通常会导致推动它们的人蒙受损失。 - The losses stem largely from the fact that the technology’s newness renders the extent and timing of its impact unpredictable. This in turn makes it easy to judge companies too positively amid all the enthusiasm and difficult to know which will emerge as winners when the dust settles.

亏损主要源于这项技术的新颖性,使其影响的程度和时间难以预测。这反过来又使得在一片热情中轻易对公司做出过于乐观的判断,而在热潮退去后,也难以确定哪些公司会成为最终的赢家。 - There can be no way to participate fully in the potential benefits from the new technology without being exposed to the losses that will arise if the enthusiasm and thus investors’ behavior prove to have been excessive.

如果不承担因热情过度、投资者行为失当而导致损失的风险,就无法充分参与新技术带来的潜在收益。 - The use of debt in this process – which the high level of uncertainty usually precluded in past technological revolutions – has the potential to magnify all of the above this time.

此次在这一过程中使用债务——而以往的技术革命通常因不确定性过高而避免使用债务——有可能放大上述所有风险。

Since no one can say definitively whether this is a bubble, I’d advise that no one should go all-in without acknowledging that they face the risk of ruin if things go badly. But by the same token, no one should stay all-out and risk missing out on one of the great technological steps forward. A moderate position, applied with selectivity and prudence, seems like the best approach.

由于没有人能确切判断这是否是一场泡沫,我建议任何人都不应孤注一掷,同时必须承认,一旦事态恶化,自己可能面临毁灭性的风险。但同样地,也无人应完全置身事外,以免错失一次重大的技术飞跃。采取一种适度、有选择性且谨慎的态度,似乎是最佳策略。

Finally, it’s essential to bear in mind that there are no magic words in investing. These days, people promoting real estate funds say, “Office buildings are so yesterday, but we’re investing in the future through data centers,” whereupon everyone nods in agreement. But data centers can be in shortage or in oversupply, and rental rates can surprise to the upside or the downside. As a result, they can be profitable… or not. Intelligent investment in data centers, and thus in AI – like everything else – requires sober, insightful judgment and skillful implementation.

最后,必须牢记:投资中并不存在什么神奇的秘诀。如今,推广房地产基金的人常说:“办公楼早已过时,我们正通过数据中心投资未来。”于是众人纷纷点头赞同。但数据中心也可能出现短缺或产能过剩,租金水平也可能意外上扬或下跌。因此,它们可能盈利……也可能不盈利。对数据中心进行明智投资,进而对人工智能进行投资——和所有其他领域一样——都需要冷静、深刻的判断力以及娴熟的执行能力。

December 9, 2025

P.S.: The following has nothing to do with the financial markets or the question of whether AI is the subject of a bubble. My topic is the impact of AI on society through joblessness and purposelessness. You needn’t read it – that’s why it’s a postscript – but it’s important to me, and I’ve been looking for a place to say a few words about it.

附注:以下内容与金融市场或人工智能是否泡沫无关。我的主题是人工智能对社会的影响,尤其是失业与意义缺失的问题。你不必阅读这段文字——正因如此它才被放在附注里——但对我而言很重要,我一直想找一个地方谈谈这些想法。

On November 18, a research note from Barclays described Fed Governor Christopher Waller as having “highlighted how recent stock market enthusiasm around AI has not yet translated into job creation.” This strikes me as paradoxical given my sense that one of AI’s main impacts will be to increase productivity and thus eliminate jobs. That is the source of my concern.

11 月 18 日,巴克莱银行发布的一份研究报告将美联储理事克里斯托弗·沃勒描述为“指出了近期市场对人工智能的热衷尚未转化为就业增长”。这让我感到矛盾,因为我认为人工智能的主要影响之一将是提高生产率,从而导致岗位减少。这正是我担忧的根源。

I view AI primarily as an incredible labor-saving device. Joe Davis, Global Chief Economist and Global Head of the Investment Strategy Group at Vanguard, says, “for most jobs – likely four out of five – AI’s impact will result in a mixture of innovation and automation, and could save about 43% of the time people currently spend on their work tasks.” (Exponential View, September 3)

我认为人工智能本质上是一种极强的省力工具。先锋集团全球首席经济学家兼投资策略集团全球负责人乔·戴维斯表示:“对于大多数工作——可能有五分之四——人工智能的影响将表现为创新与自动化的结合,可能使人们目前用于工作任务的时间节省约 43%。”(《指数视野》,9 月 3 日)

I find the resulting outlook for employment terrifying. I am enormously concerned about what will happen to the people whose jobs AI renders unnecessary, or who can’t find jobs because of it. The optimists argue that “new jobs have always materialized after past technological advances.” I hope that’ll hold true in the case of AI, but hope isn’t much to hang one’s hat on, and I have trouble figuring out where those jobs will come from. Of course, I’m not much of a futurist or a financial optimist, and that’s why it’s a good thing I shifted from equities to bonds in 1978.

我对就业前景的展望感到恐惧。我极为担忧那些因人工智能而变得不再需要工作,或因此找不到工作的人员。乐观者认为“每次过去的技术进步之后,总会出现新的工作岗位”。我希望在人工智能的情况下这一规律依然成立,但仅靠希望来支撑是远远不够的,而且我也很难想象这些新工作究竟会从何而来。当然,我并非什么未来学家,也不是金融乐观主义者,这正是我在 1978 年从股票转向债券的明智之处。

The other thing the optimists say is that “the beneficial impact of AI on productivity will cause a huge acceleration in GDP growth.” Here I have specific quibbles:

乐观者还声称:“人工智能对生产率的积极影响将导致 GDP 增长出现巨大加速。”对此,我有具体的质疑:

- The change in GDP can be thought of as the change in hours worked times the change in output per hour (aka “productivity”). The role of AI in increasing productivity means it will take fewer hours worked – meaning fewer workers – to produce the goods we need.

GDP 的变化可以理解为工作小时数的变化乘以每小时产出的变化(即“生产率”)。人工智能在提高生产率方面的作用意味着,生产我们所需商品所需的工作时数将减少——这意味着需要的工人数量也会减少。 - Or, viewed from the other direction, maybe the boom in productivity will mean a lot more goods can be produced with the same amount of labor. But if a lot of jobs are lost to AI, how will people be able to afford the additional goods AI enables to be produced?

或者从另一个角度来看,生产率的提升可能意味着用相同数量的劳动力能够生产出更多商品。但如果大量工作被人工智能取代,人们又如何负担得起人工智能所催生的额外商品呢?

I find it hard to imagine a world in which AI works shoulder-to-shoulder with all the people who are employed today. How can employment not decline? AI is likely to replace large numbers of entry-level workers, people who process paper without applying judgment, and junior lawyers who scour the lawbooks for precedents. Maybe even junior investment analysts who create spreadsheets and compile presentation materials. It’s said that AI can read an MRI better than the average doctor. Driving is one of the most populous professions in America, and driverless vehicles are already arriving; where will all the people who currently drive taxis, limos, buses, and trucks find jobs?

我很难想象一个世界,人工智能会与当今所有就业人员并肩工作。就业率怎么可能不下降?人工智能很可能会取代大量初级员工、那些仅处理文件而不需判断力的工作人员,以及翻阅法律书籍寻找判例的初级律师。甚至可能还包括制作电子表格和整理演示材料的初级投资分析师。据说,人工智能读取核磁共振图像的能力已超过普通医生。驾驶是美国人口最多的行业之一,而无人驾驶车辆已经出现;如今开出租车、豪华轿车、公交车和卡车的人们,将来会去哪里找工作?

I imagine government’s response will be something called “universal basic income.” The government will simply mail checks to the millions for whom there are no jobs. But the worrier in me finds problems in this, too:

我设想政府的回应将是一种被称为“全民基本收入”的政策。政府会直接向数百万找不到工作的人邮寄支票。但让我担忧的是,这同样存在诸多问题:

- Where will the money come from for those checks? The job losses I foresee imply reduced income tax receipts and increased spending on entitlements. This puts a further burden on the declining segment of the population that is working and implies even greater deficits ahead. In this new world, will governments be able to fund ever-increasing deficits?

这些支票的资金从何而来?我预见的失业潮意味着税收收入减少,同时福利支出增加。这将进一步加重仍在工作的那部分不断萎缩的人口的负担,并预示着未来更大的财政赤字。在这个新世界里,政府还能否承担日益增长的赤字? - And more importantly, people get a lot more from jobs than just a paycheck. A job gives them a reason to get up in the morning, imparts structure to their day, gives them a productive role in society and self-respect, and presents them with challenges, the overcoming of which provides satisfaction. How will these things be replaced? I worry about large numbers of people receiving subsistence checks and sitting around idle all day. I worry about the correlation between the loss of jobs in mining and manufacturing in recent decades and the incidence of opioid addiction and shortening of lifespans.

更重要的是,工作带给人们的远不止一份薪水。工作给了人们早起的理由,为他们的一天赋予结构,使他们在社会中扮演有成效的角色并获得自尊,同时带来挑战,克服这些挑战能带来满足感。这些价值又将如何被替代?我担心大量的人只靠基本生活补助过活,整天无所事事。我也担心近几十年来采矿和制造业岗位的流失与阿片类药物成瘾率上升、人均寿命缩短之间的关联。

And by the way, if we eliminate large numbers of junior lawyers, analysts, and doctors, where will we get the experienced veterans capable of solving serious problems requiring judgment and pattern recognition honed over decades?

顺便说一句,如果我们裁掉大量初级律师、分析师和医生,那么从哪里去找那些具备丰富经验、能够解决需要数十年判断力和模式识别能力的严重问题的资深人才?

What jobs won’t be eliminated? What careers should our children and grandchildren prepare for? Think about the jobs that machines can’t perform. My list starts with plumbers, electricians, and masseurs –physical tasks. Maybe nurses will earn more than doctors because they deliver hands-on care. And what distinguishes the best artists, athletes, doctors, lawyers, and hopefully investors? I think it’s something called talent or insight, which AI might or might not be able to replicate. But how many people at the top of those professions are needed? A past presidential candidate said he would give laptops to everyone who lost their job to offshoring. How many laptop operators do we need?

哪些工作不会被消除?我们的孩子和孙辈应该为哪些职业做准备?想想机器无法完成的工作。我的清单从水管工、电工和按摩师这些体力工作开始。也许护士的收入会超过医生,因为她们提供的是直接的护理服务。而最优秀的艺术家、运动员、医生、律师,以及希望成为的投资者,究竟有何不同?我认为是某种被称为天赋或洞察力的东西,人工智能或许能模仿,或许不能。但那些顶尖职业中,真正需要多少人呢?一位过去的总统候选人曾表示,他要给每个因外包而失业的人发一台笔记本电脑。我们到底需要多少个笔记本电脑操作员?

Finally, I’m concerned that a small number of highly educated multi-billionaires living on the coasts will be viewed as having created technology that puts millions out of work. This promises even more social and political division than we have now, making the world ripe for populist demagoguery.

最后,我担心的是,少数居住在沿海地区的高学历亿万富翁将被视为创造了使数百万人失业的技术。这势必会带来比现在更严重的社会与政治分裂,使世界更容易陷入民粹主义的煽动之中。

I’ve seen incredible progress over the course of my lifetime, but in many ways I miss the simpler world I grew up in. I worry that this will be another big one. I get no pleasure from this recitation. Will the optimists please explain why I’m wrong?

我一生中见证了惊人的进步,但在许多方面,我却怀念自己成长的那个更简单的世界。我担心这又会成为另一个重大的转折点。我并不从中获得任何愉悦。请乐观主义者解释一下,为什么我是错的?

Interestingly in this connection, Vanguard’s Joe Davis points out that more Americans are turning 65 in 2025 than in any preceding year, and that approximately 16 million baby boomers will retire between now and 2035. Could AI merely make up for that? There’s an optimistic take for you.

有趣的是,维京集团的乔·戴维斯指出,2025 年有更多美国人达到 65 岁,超过了以往任何一年;大约 1600 万婴儿潮一代将在当前至 2035 年间退休。人工智能真能弥补这一缺口吗?这就是一个乐观的视角了。

HM

© 2025 Oaktree Capital Management, L.P.

© 2025 奥克特资本管理有限公司